In the last blog we looked at Frank Lloyd Wright, a celebrated twentieth century American architect, who also excelled as a landscape designer. Lloyd designed wonderful gardens for some of his most iconic houses. In this blog we look at Isamu Noguchi, another cross disciplinary design master, practicing as a landscape designer.

In the last blog we looked at Frank Lloyd Wright, a celebrated twentieth century American architect, who also excelled as a landscape designer. Lloyd designed wonderful gardens for some of his most iconic houses. In this blog we look at Isamu Noguchi, another cross disciplinary design master, practicing as a landscape designer.

Noguchi was one of the most versatile artists of the modern era. In a career spanning six decades he explored many areas of art and design, including landscape design, sculpture, drawing, ceramics, photography, theatre stage sets, playgrounds, and furniture.

Noguchi first saw the possibilities for the landscape as a sculptural space in 1931, when he returned to Japan for the first time since his childhood. He visited the city’s gardens, including the famous Zen garden at Ryoanji and the Silver Pavilion at Gingkakuji with its unique sand formations. The gardens, particularly the Stroll Gardens, taught Noguchi that sculpture need not be placed on a pedestal but could extend all around – to be walked on and through. The gardens offered spaces in which the viewer could become a participant in the work as it presented ever changing spatial and temporal relationships.

Noguchi was also deeply affected by the grave mounds of Japan. Their earthen medium, simple geometry, and ritual purpose offered Noguchi a prototype for his work as a landscape designer, integrating man, nature, and sculpture. The possibility of working with the landscape had captured his imagination, “I think that the creation of art is an intimate involvement between matter and man. He emerges out of the mud and he finds his way.”

Two wonderful examples of Isamu Noguchi’s work as a landscape designer are the UNESCO Japanese Garden of Peace in Paris and California Scenario Garden. Both are public gardens that show how Noguchi integrated a Japanese aesthetic with western abstract art.

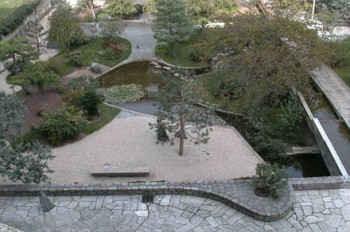

The UNESCO garden designed by Noguchi and donated by the Japanese government is marked throughout by the Japanese spirit, while at the same time expressing Noguchi’s individual artistic creativity. Unlike traditional Japanese garden it can be viewed as a whole from the platform or upper garden. The garden has three axes: the axis from the platform to the place set aside for the open-air tea ceremony, the axis of the flowery path and the stream, and the axis from the rounded bridge to the lantern that passes through the place set aside for the open air tea ceremony. In traditional Japanese gardens the boundaries between different materials and spaces are kept deliberately vague, but Noguchi’s garden has clearly defined boundaries. Each space is a profound expression of Japanese culture and taste, while also presenting as individual sculptures. The way in which the rocks are laid out and the plant selection is however essentially Japanese and enable visitors to appreciate the passing seasons.

In 1979 Noguchi was asked to design a public garden to enhance two office towers on land once used as a lima bean farm. Noguchi created a simple stone plaza with a few green spaces. Noguchi first conceived the project as an “abstract metaphor for the state of California, from the Sierras, to the desert, to the woods. In addition to including redwoods and cacti, among other native plants, it encompasses a number of individual elements designed by the artist to evoke some of California’s salient characteristics.”

The garden features a crack filled with water and stones, which functions as a stream beginning at the thirty foot high sandstone triangle named Water Source and ending at Water Use, a granite wedge. Forest Walk takes visitors past a patch of California redwoods and Desert Land features a symmetrical mound planted with a variety of cacti, agave and other desert plants. The sculpture Spirit of the Lima Bean, constructed of twelve feet high granite boulders, educates visitors about the earlier use of the site.

As a landscape designer Isamu Noguchi allowed human creativity to take precedence over nature. Noguchi merged the disciplines of architecture, landscape design, industrial design and sculpture long before the era of post modernism when cross disciplinary work became common place, deftly moving between and merging the different disciplines throughout his long career.